KOMAGATA MARU: INTERSECTIONALITY AND THE ARTS

As a first generation Indo-Canadian, my identity resides at the intersection of my Canadian and Indian selves. These two identities, coupled with my Sikh religious identity, provide multiple vantage points from which to view the world. In the past I strove to keep these identities separate, but as I mature artistically, these identities have melded together into a unique worldview. This merging of identities inspired my artistic work, Komagata Maru, which uses music to explore themes of social justice and activism. The work marks the centenary of the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, when 376 passengers from India traveled by ship to Canada but were barred from immigrating because of racist laws.

Drawing artistic influence from seemingly dissimilar sources has become more commonplace, as technologies such as the Internet connect individuals globally; however, the lexicon to describe such movements has progressed only minimally. In music, the dreaded “f-word,” fusion, is often used as a catchall term for any type of inter-genre practice. This word is often mistakenly used to define simple collaboration rather than a true melding of multiple elements to create a single entity as the word fusion suggests. Rather than perpetuate the misuse of “fusion,” this paper seeks to contextualize the term “intersectionality,” while exploring how it establishes a framework within which to contextualize my artistic practice.

INTERSECTIONALITY

Noted UCLA and Columbia Law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” to examine race and gender politics (and later class, sexual orientation, age and color) as they pertain to the experience of Black women in America.1 Crenshaw uses this term in order to counteract the distortion of a “single axis-analysis” of experience with that of “the multidimensionality of Black… experiences.”2 The act of distilling an individual’s experience down to a single word misrepresents that experience, as no one term can fully capture the complexity of a personal narrative — this often occurs through generalizations related to gender or race, for example.

Crenshaw’s above statement about “multidimensionality” can be said to exist in the definitions found in musical genres and practices. The term “jazz,” for instance, can be used to describe many types of music from Dixieland to free improvisation. Simply using the term jazz as a descriptor is not enough to describe anyone’s music. Nathaniel Mackey, in the book Jazz Among the Discourses, points out that:

The recent ascendancy of cultural studies in academia tends to privilege collectivity and group definition over individual agency and self-expression, to see individual expression as a reflection of group definition. In relating the two, however, we should remember that in matters of artistic othering, individual expression both reflects and redefines the collective, realigns, refracts it.3

Thus, the study of jazz history, in this case, is not one of collective movements, but rather that of the individual. Any description of a type of music that is unidimensional, or reliant on one over-simplified category, is grossly insufficient. Utilizing Crenshaw’s term “intersectionality” is particularly useful in describing multidimensional artwork and pays respect to the individual’s unique experience. In the Indian classical tradition, one learns within a gharana (a school of music with a set of characteristic stylistic features),4 but this training does not simply create artistic carbon copies of one’s teacher. One’s individuality is always present and compels the artist to find his or her own way through the tradition.

Neelamjit Dhillon, promotional image for Komagata Maru, August 2013, photo by Hamin Honari with photo from Vancouver Public Library archives, layout by Preet Mangat. Image courtesy the artist

INDIAN CLASSICAL AND JAZZ

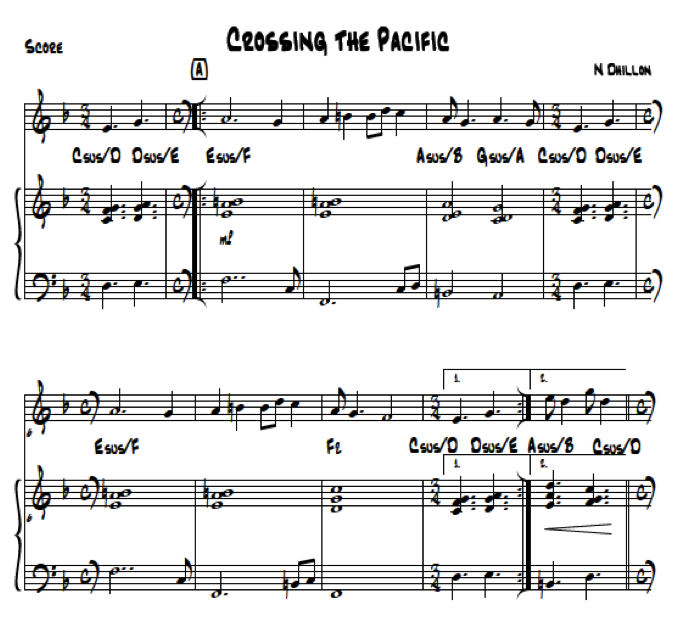

The use of intersectionality in the Komagata Maru work can be seen in two ways. The first way is concerned with the process in which Indian classical and jazz elements manifest musically. Both styles set improvisation within parameters that outline melodic and rhythmic structures within which the musician is free to spontaneously create. The melodic framework — the notes available from which to draw one’s melodic choices — in Indian classical music is called raag and in jazz is represented by the concept of harmony. The rhythmic framework, the beat cycle within which to create, is called taal in Indian classical music; in jazz it is represented by the formal structure of a piece. One can improvise within a twelve beat rhythmic cycle in Indian classical music the same way that one creates melodies upon a twelve-bar blues form. Within the music for Komagata Maru, harmonic structures are used to create chords that reflect the rules of the raag in which a piece has been set and Indian rhythmic cycles create forms upon which to improvise. The movement Crossing the Pacific is set in raag Yeman and taal Pancham Swari of 15 beats. For me, raag Yeman expresses the moods of hope and optimism, which the passengers may have felt, and the 15-beat rhythmic cycle depicts the perils involved in the journey.

Neelamjit Dhillon, first section of Crossing the Pacific from Komagata Maru

JAZZ AND SIKHISM

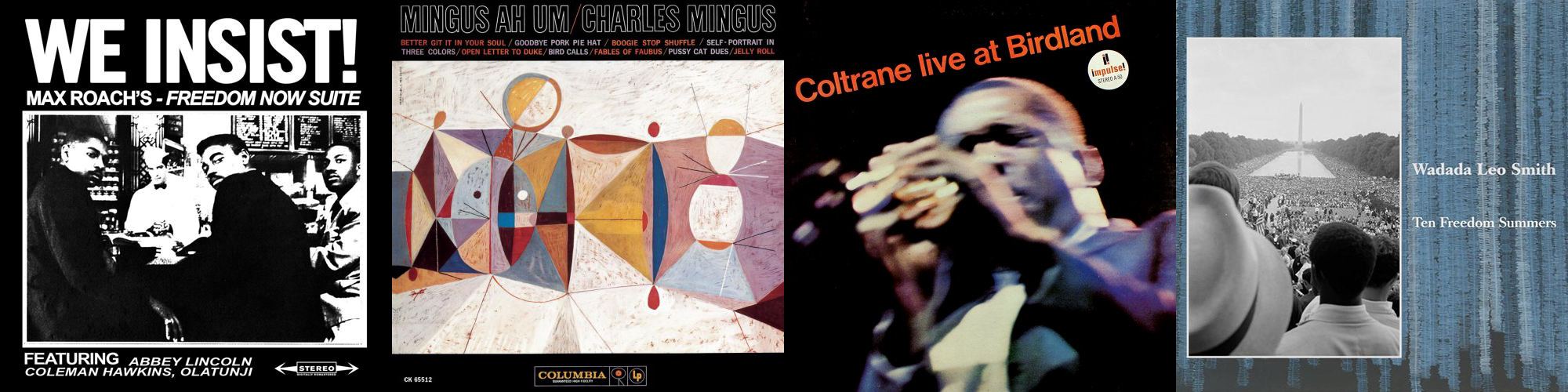

The second way my work, Komagata Maru, makes use of intersectionality is through jazz and Sikhism. Jazz was used as a voice for the civil rights movement and many works such as the album We Insist! by Max Roach, the piece Fables of Faubus by Charles Mingus, the piece Alabama by John Coltrane and the four-disc box set Ten Freedom Summers by Wadada Leo Smith, as well as countless others, employ music as a vehicle for activism and as a method for commenting on and raising awareness for the struggle for equal rights. Sikhism is a theology that also encourages the pursuit of social justice. As stated in the Guru Granth Sahib, “Recognize the Lord’s Light within all, and do not consider social class or status; there are no classes or castes in the world hereafter.”5 The teaching of the Sikh gurus exemplifies equality amongst all people regardless of background, which provides context for me to create activist works. I seek to bring awareness to social justice issues through music in order to give audiences an opportunity to consider another perspective by reflecting on these concepts through a different lens. From that experience, I hope that the common intersections among people will galvanize us and help us realize our similarities rather than our differences.

Album covers: Max Roach, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane and Leo Smith

My art is a reflection of my life and is born out of the intersection of my various identities and the ways in which those identities interact and influence one another. By using the languages of Indian classical music and jazz, improvisation becomes the medium with which to comment, in real time, on the present experience. My artistic practice, either demonstrated by my piece Wisconsin about the 2012 shooting at the Oak Creek gurdwara (Sikh house of worship) or by my Komagata Maru suite, provides me an outlet with which to express what it means to be an Indo-Canadian Sikh and how, through music, that experience can help others understand the intersection of their own lives and enable a more equitable society. Komagata Maru not only reflects upon what happened a century ago, but also delivers a call to action so that such a deed is never again perpetrated against any marginalized community.

Neelamjit Dhillon Quartet, Museum of Vancouver, Indian Summer Festival, July 6, 2014, photo by Tom Delamere

NOTES

1. Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review, 1991, 1.

2. Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” U. Chi. Legal F., 1989, 1.

3. Nathaniel Mackey, “Jazz: From Noun to Verb,” in Krin Gabbard, Jazz Among the Discourses (Duke University Press, 1995), 97.

4. Sandeep Bagchee, Nad: Understanding Raga Music, 1st edition (Mumbai: Eshwar, 1998), 329329.

5. Guru Nanak, “SikhiToTheMAX,” accessed May 15, 2014: http://www.sikhitothemax.com/page.asp?ShabadID=1372.

Images courtesy the author